Has Partial Birth Abortions Become Legal Again

life after roe

Everything You Need to Know About the Abortion Debate

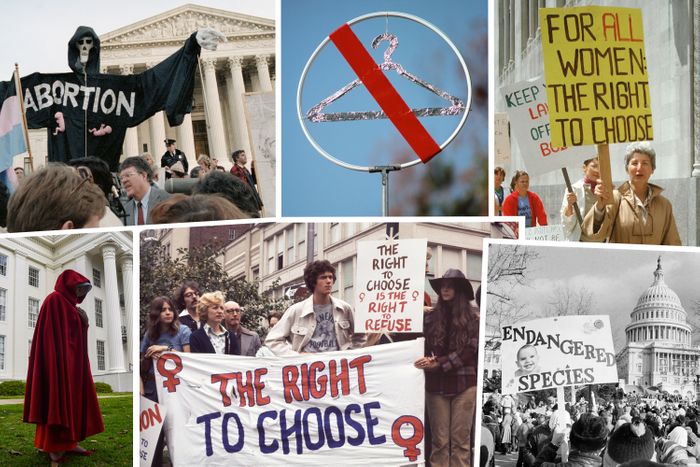

Photo: Clockwise from top left: Bettmann Archive; Viviane Moos/Corbis; Mark Meyer/LIFE; Bettmann Archive; Barbara Freeman; Julie Bennett/Getty Images

During the 49 years since the U.S. Supreme Court legalized abortion, the issue has run hot and cold in the political realm, sometimes dominating the national conversation and at other times simmering in the background as conservatives chipped away at reproductive rights and laid the groundwork for the repeal of Roe v. Wade. Now, with the leak of a draft Supreme Court majority opinion that would do just that, the issue has exploded. Pro-choice Americans are bracing for the loss of reproductive rights, and the anti-abortion movement is preparing to celebrate its long-awaited victory — and set its next targets.

If you are new to abortion politics, jumping into the decades-old debate can be overwhelming. Here are the key terms and fault lines you'll need to know.

The 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade (along with the lesser-known companion case Doe v. Bolton) codified nationally a woman's right to have an abortion under certain circumstances. The majority opinion, written by Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun with six other justices concurring, found the right to an abortion is an implied constitutional protection of privacy. It held that women had an absolute right to a first-trimester abortion (up to 14 weeks). In the second trimester (14–27 weeks), the government could impose medical regulations, strictly to protect the woman's health. Then in the third trimester, abortions could be banned outright, reflecting the state's interest in protecting the "potential life" of the fetus — but exceptions for physician-defined threats to the life or health of the woman had to be allowed.

The decision swept away state bans on most abortions in 33 states, while liberalizing abortion laws in 13 other states. It is annually commemorated on January 22 by both pro-choice and anti-abortion organizations. (Most notably, the March for Life in D.C. has taken place on this date every year since 1974.)

Fetal viability is the point in the development of the human fetus when it has the capacity to survive outside the womb. The medical rule of thumb (which many states and courts follow) is that viability occurs at the earliest at about 24 weeks of pregnancy. Less than one percent of abortions occur after fetal viability, which is why the anti-abortion movement has been determined to shift the line back to earlier stages of pregnancy.

In all the Supreme Court precedents on abortion, women have a very clear right to an abortion prior to viability, subject to limited regulations. However, in 2021 the Court refused a petition to put a hold Texas law that bans on abortions performed after 6 weeks of pregnancy, which blatantly ignores this precedent. Idaho and Oklahoma passed copycat laws in 2022.

The currently prevailing Supreme Court precedent was set in 1992 by Planned Parenthood v. Casey, a 5-4 decision that both reaffirmed and modified Roe v. Wade. Authored jointly by three Republican-appointed justices (Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O'Connor, and David Souter), with two other Republican-appointed justices concurring (Harry Blackmun and John Paul Stevens), Casey scrapped the trimester system, replacing it with a simple right to pre-viability abortions. However, Casey also allowed states to regulate abortions that occurred pre-viability, as long as those regulations did not "unduly burden" a woman's right to an abortion. (Roe had barred all government interference in the first trimester.)

Reproductive rights advocates feared the very subjective "undue burden" standard would create a big opening for abortion restrictions, but at the time, most were relieved that the Court had not, as many expected, simply reversed Roe. For the same reason, it was perceived as a bitter defeat for anti-abortion advocates, although it opened up new avenues for abortion restrictions much earlier in pregnancy.

Many, and perhaps most, anti-abortion activists embrace the idea that from the moment of conception (or fertilization) the fetus is morally and metaphysically a "person" who deserves full citizenship rights that should be constitutionally protected. In other words, while the anti-abortion movement's immediate goal is reversal of Roe v. Wade and a state-controlled landscape of abortion laws, it generally favors a national law (or constitutional amendment) entrenching fetal rights. A Human Life Amendment to the Constitution has been endorsed in national Republican platforms dating back to 1980.

A state-based "personhood movement" has aimed to enshrine fetal rights in state constitutions, leading to unsuccessful ballot initiatives in Colorado, Mississippi, and North Dakota, and a successful (if vaguer) initiative in Alabama. The "personhood movement" tends to take particularly extreme positions on fetal and embryonic life, often opposing IV-fertilization practices that lead to the destruction of unused embryos, along with birth control methods (e.g., IUDs and morning-after pills) it regards as abortifacient rather than contraceptive. Significantly, the "sanctuary city for the unborn" movement in Texas, which led to the state's abortion ban, often sought local ordinances banning the sale of morning-after pills and all abortions.

One type of state law (and congressional proposal) has aimed to chip away at abortion rights by shifting the dividing line between legal and potentially illegal abortions from fetal viability to some earlier point in pregnancy — most popularly a scientifically unsubstantiated point at which a fetus is alleged to be capable of experiencing pain (typically 20 or 22 weeks into pregnancy).

The most popular current model for state abortion bans is an even more dubious proposition: prohibiting abortion when, in theory, a fetal heartbeat can be detected. (Though cardiac activity — or pulsing cells — can be detected via ultrasound as early as six weeks, this term is misleading because embryos don't have hearts.) Typically these "heartbeat bills" ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy, which is before many women know they are pregnant. Like the fetal-pain bans, these laws are intended to supply agitprop to the anti-abortion cause, and provide a suggested new standard for future abortion restrictions. So far eleven states have enacted "heartbeat" laws.

Within the anti-abortion movement, there is a perpetually raging debate over whether it's immoral to accept exceptions to proposed abortion bans for pregnancies resulting from rape and incest. Such exceptions are extremely popular, and Republican politicians (including Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump) tend to support them. There's so much talk about these exceptions in conservative circles that those who embrace them have been able to cultivate a "moderate" image despite supporting bans on the estimated 98.5 percent of abortions that do not involve rape or incest.

Several recently passed state laws – including the Texas 6-week ban that the Supreme Court allowed to take effect, and the Mississippi 15-week ban at issue in Dobbs – have no rape or incest exceptions.

Largely frustrated in their efforts to directly ban or restrict abortions after Casey, Republican-controlled states increasingly focused their efforts on making abortion services unavailable. The idea behind TRAP (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) laws was to devise ostensibly reasonable-sounding requirements, usually rationalized as being for the benefit of the women involved, that had the effect of shutting down abortion clinics. As the Guttmacher Institute explains:

Most TRAP laws apply a state's standards for ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) to abortion clinics, even though surgical centers tend to provide riskier, more invasive procedures and use higher levels of sedation. In some cases, TRAP laws also extend to physicians' offices where abortions are performed and even to sites where only medication abortion is administered. TRAP regulations often include minimum measurements for room size and corridor width — requirements that may necessitate relocation or costly changes to a clinic's physical layout and structure. Some regulations also mandate that clinicians performing abortions have admitting privileges at a local hospital, even though complications from abortion that require hospital admission are rare, so abortion providers are unlikely to meet minimum annual patient admissions that some hospitals require. TRAP requirements set standards that are intended to be difficult, if not impossible, for providers to meet. Instead of improving patient care, these laws endanger patients by reducing the total number of abortion facilities that are able to stay open under these financial and administrative constraints, thus making safe services harder to obtain.

In 2016, with Justice Kennedy supplying the key vote, the Supreme Court put up a stop sign to TRAP laws in a Texas case by challenging the states' right to mischaracterize restrictions that were transparently intended to reduce access to abortion services (a textbook case of "undue burden"). After Justice Kennedy was replaced by Brett Kavanaugh, a nearly identical law enacted by Louisiana was invalidated by the Court in a 5-4 decision in 2020, with Chief Justice John Roberts joining the liberal minority, pretty clearly because he thought it would be disruptive to reverse course so abruptly.

The vigilante enforcement scheme in the new Texas abortion law (private citizens are given a civil right of action and even bonuses for successful litigation against abortion providers who violate the 6-week ban) is reminiscent of TRAP laws insofar as it is aimed at intimidating and imposing prohibitive costs on providers. But the anti-abortion movement's focus shifted from indirect to direct attacks on legalized abortion in recent years, especially once the Court said it would review Dobbs.

This is a political, not a medical, term for abortions involving a technique (intact dilation and extraction) in which the fetus is temporarily outside the woman before the pregnancy is terminated. After striking down a state "partial-birth abortion ban" for its failure to provide an exception for the health of a woman, in 2007 the Supreme Court upheld a similar federal ban in a surprise 5-4 decision, Gonzalez v. Carhart. The Court held that the ban did not constitute an "undue burden," as alternative abortion methods were still available, and cited a congressional "finding" that the procedure was never medically necessary. (This contradicted the medical community's consensus, and did away with the traditional deference to the judgement of a woman's physician).

The anti-abortion movement has long sought to undermine support for abortion rights generally by focusing on and demonizing late-term abortions — though, as noted above, less than one percent of abortions occur after fetal viability, and these cases typically involve threats to the health of the mother or severe fetal abnormalities.

The latest impetus for an attack on late-term abortions arose when New York sought to codify abortion rights in case Roe v. Wade is reversed, passing a law in 2019 that allows for late-term abortions under strict medical circumstances (as did a proposed law in Virginia). Anti-abortion advocates, including then-President Trump, began describing such abortions as a form of "infanticide," making lurid and wildly inaccurate claims about what the procedure entails.

This congressional appropriations rider, which has been in effect since 1980, prohibits the use of federal funding for abortion services (which means abortions are not covered by Medicaid, the federal-and-state-funded health-insurance program for low-income Americans). It originally drew significant Democratic support, not just from anti-abortion Democrats but from those who viewed a funding ban as a reasonable compromise despite its heavy impact on women who could not otherwise afford abortions.

Calls for the repeal of the Hyde Amendment have now become very common among Democrats (it was a plank in the Democratic platform for the first time in 2016), to the point that 2020 presidential candidate Joe Biden reversed his long-standing position favoring the amendment. He followed through as president by proposing an end to Hyde as part of his Fiscal Year 2022 budget resolution. Meanwhile Republicans, who almost universally support Hyde, rationalize demands for a funding cutoff for Planned Parenthood as a logical extension of the law.

The Planned Parenthood Federation is a nonprofit organization that performs more abortion procedures (332,000 in 2017) than any other single provider. Through its 600 clinics, it also supplies an array of medical services, from cancer screenings to contraceptives to STI treatment to sex education. In many medically underserved areas, Planned Parenthood is the only source of reproductive-health services for poorer people.

The anti-abortion movement has tried, unsuccessfully, to defund Planned Parenthood entirely at the federal and state levels, arguing that providing any government funding just frees up money for abortion services (the Hyde Amendment already bans the use of Medicaid dollars for abortion). A sketchy 2015 "sting" operation producing video purporting to show Planned Parenthood officials discussing sales of fetal tissue (or as the anti-abortion activists called it, "baby parts") as a profit center helped inflame a fresh round of Republican attacks on Planned Parenthood in the last few years.

The preeminent pro-choice organization in the country is NARAL (National Abortion Rights Action League) Pro-Choice America, which prior to Roe v. Wade was called the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws. Other notable pro-choice groups include EMILY's List, a political organization that exclusively funds campaigns waged by pro-choice Democratic women; the research-oriented Guttmacher Institute; the Center for Reproductive Rights, a legal organization that handles litigation in abortion and contraception cases; and the National Network of Abortion Funds, which helps pay for abortions for women who cannot otherwise afford them.

The movement to restrict abortions has multiple organizing outlets. The National Right to Life Committee is the oldest and broadest-based group, which often promotes pragmatic strategies for gradually eroding abortion rights and focusing public attention on controversial practices like rare late-term abortions and questionable-sounding motives for abortion. A more militant organization, the Susan B. Anthony List, views itself as a counterpart to EMILY's List. A number of explicitly religious organizations, notably the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (which helped create the NRLC), the Southern Baptist Convention, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, have been active in the fight against legal abortion. Personhood USA is a group dedicated to the radical cause of establishing fetal personhood in the Constitution and laws.

Arguments over language have long been part of the abortion debate. The most frequently used term for those who want to protect a fundamental right to an abortion has always been "pro-choice." But more recently, a perceived need to become less defensive about the abortion "choice," and to frame abortion as a normal health service, has led to the greater use of more straightforward terms like "reproductive rights" or "abortion rights." (And a push to avoid calling the opposing side "pro-life," using the terms "anti-abortion" or "anti-choice" instead.) An example of the impact of this more positive point of view was the elimination in 2012 of the Democratic national platform pledge to make abortion (in Bill Clinton's words) "safe, legal and rare." "Pro-life" remains the preferred self-designation for virtually all activists who oppose abortion.

This piece has been updated throughout.

- Nancy Pelosi Communion Ban Is a Challenge to Pope Francis

- Oklahoma Outdoes Itself in Race to Wipe Out Abortion Rights

- I, Too, Have a Human Form

Source: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2022/05/abortion-debate-everything-you-need-to-know.html